April 29, 2021

Old New England Cemetery Lore: Watch Your Step

April 18, 2021

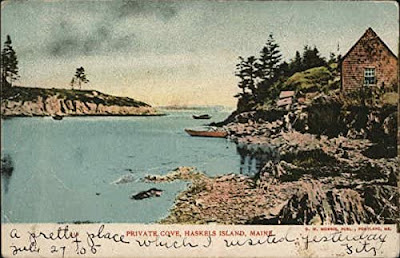

Rats, Cats, and Death: Horror on Haskell Island

Haskell Island is located off the coast of Harpswell, Maine. It's a small island, and apparently has no full time residents these days, just vacation homes. It looks quite idyllic, but like many quaint New England locales Haskell Island has a strange past.

According to legend, the island was first colonized by the two Haskell brothers, way back in the 1600s. The Hakells were very industrious and transformed the island into an agricultural paradise. They planted an orchard, plowed the land into fertile fields, and fished in Casco Bay. The brothers prospered in their little Eden.

Unfortunately, one day they accidentally brought some rats to the island in their boat while transporting supplies. Haskell Island had everything the rats could want: food, water, places to nest, and no predators. The rats multiplied rapidly and soon threatened the brothers' livelihood.

Antique Haskell Island postcard from Amazon. "A pretty place which I visited yesterday..."

To stop the rats, the Haskell brothers brought a couple of cats to their island. The brothers didn't provide any food for the cats and expected them to survive by killing rats. The cats met their expectations. They ate rats, and there were so many rats that the cats thrived and multiplied. Soon there were more cats than rats, and eventually there were no rats left at all, just an island full of hungry cats.

The cats roved the island, howling with hunger. They climbed the apple trees, roamed the fields, and paced the shore, looking for something to kill and eat.

The Haskell brothers had to do something about the ravenous felines, but something happened before they could devise a plan: one of them became sick. He fell seriously ill, so his brother took the boat and went to the mainland to get a physician. "Hurry back," the sick brother said weakly as he lay in bed.

Can you see where this is going? An island full of hungry cats, an incapacitated man lying weak and helpless in bed? When the healthy brother returned to the island, he and the physician were horrified by what they found inside the Haskells' house. The sick brother had been ripped to shreds, and the cats were tearing the last morsels of flesh from his body. At last their hunger was sated.

*****

It's a simple little story, but really resonates with me. It appears in Horace Beck's 1957 book The Folklore of Maine. The Maine Encyclopedia says Haskell Island was named for a Captain Haskell who purchased, but never lived on, the island, so I don't think the man-eating cat story is true. Still, it has the power of a good horror movie, and reads like an environmentalist fable. The brothers try to master the island, but end up doomed by their own actions and the invasive species they brought to the island.

It reminds me of "Bart the Mother," a 1998 episode of The Simpsons where Springfield is overrun by ravenous lizards. At first people are happy because the lizards eat all the pigeons, but then realize they'll need to import snakes to eat the lizards, and then gorillas to eat the snakes...

Horace Beck notes that there is a coda to the story. According to some people, the sick brother was not killed by cats, but by pirates. He had seen the pirates burying their treasure on Haskell Island, and they killed him to keep their secret safe. Then they made it look like the cats had done it to deflect attention. I don't find that explanation quite as compelling, though. The story is structured like a version of "I Know an Old Lady Who Swallowed A Spider," and randomly introducing pirates just doesn't make sense.

April 11, 2021

Mountain Ash, or the Witch-Wood Tree

Although it's now socially acceptable to be a witch, that wasn't always the case, particularly here in New England. Many people today identify as witches, which usually means they are interested in the occult, folk magic, and possibly paganism. These are all good things, and most modern witches are lovely people who just want to be left alone with their candles and dried herbs.

In the past, though, no one wanted to be called a witch. The activities we associate with modern witches today - fortune telling, herbal magic, protection magic - were widely practiced across New England, sometimes by specialists called cunning folk, conjurers or seers, but more often just by average people. Curious to know if you were going to marry the boy next door? Grandma would break out the Bible, bind a key inside it, and start asking questions. Troubled by bad dreams? The farmer next door would tell you to place a knife under the bed. Everyone knew a charm or two, but no one called themself a witch.

This is because people believed witches used magic for evil: ruining crops, killing farm animals, making children sick, and causing death. Sometimes witches were motivated by jealousy, sometimes revenge, and sometimes they were working for the Devil himself. No one wanted to be a witch. Calling yourself a witch in the past would be like saying, "Hi! I'm a serial killer" today.

|

| Image from the Arbor Day Foundation. |

A community might accuse its most unpopular members of being witches, but these accusations were always false and motivated by the need to blame someone for life's misfortunes. Crops failed? Blame the mean old widow down the road and call her a witch. Child sick? Blame the crotchety guy who swears at everyone - he must be a witch.

These people weren't really witches, but there was plenty of magic for protecting one's home and family from the imaginary threat. A horseshoe placed above the front door was the most popular method, but there were others, including this one I found in Clifton Johnson's What They Say in New England (1896):

It is well to have a piece of a branch cut from a mountain ash in the house. It is as good to keep to witches as a horseshoe nailed over the door.

The practice seems to have been relatively widespread. John McNab Currier was a physician and folklorist who lived in New Hampshire in the 19th century. Currier knew a woman who blamed witches for all the misfortunes in her life and wore a necklace of mountain ash beads to deflect their evil influence:

They were cut about three eighths of an inch in length, the bark being left on, and strung on string running through the pith. She was careful to keep them concealed, but sometimes they would work up above her collar and be conspicuous. This species of tree was once quite popular among New England witch-believers as a charm against witches... (“Contributions to New England Folk-Lore,” The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 4, No. 14 (Jul – Sep. 1891)

Folklorist Fanny Bergen also notes that many people carried pieces of mountain ash wood in their pockets and the tree was sometimes called the "witch-wood" tree (“Some Bits of Plant-Lore”, The Journal of American Folklore, Vol 5, No. 16 (Jan – Mar, 1892).

|

| Image from the Arbor Day Foundation |

Although many folks still hang lucky horseshoes over their doorways, I haven't encountered anyone who carries around pieces of mountain ash, let alone wears a necklace made of it. Partly it's because we don't practice as much folk magic as our ancestors did, and even when we do the meaning has changed. People who hang horseshoes today usually do so to bring luck, not to keep out witches. We just aren't as afraid of witches as we once were, which is a good thing.

I also think New Englanders, and Americans in general, are less familiar with trees and plants than we were were a century ago. Very few of us work in agriculture or even outdoors, so we don't need to be well-acquainted with what's growing around us. Industrial and scientific progress has made us less superstitious (and less likely to hang our neighbors as witches), but it's also disconnected us from our immediate environment.

Even if I wanted to make a mountain ash necklace, I probably couldn't identify the tree. They tend to grow in higher elevations, and I've lived most of my life in the coastal regions. The mountain ash (sorbus americana) is a small tree that bears orangey red berries. Sorbus Americana is very similar to the European rowan tree, which has a lot of magical lore attached to it, and I assume that's why magical powers are ascribed to the mountain ash.

There's a mountain ash tree nearby me in Arnold Arboretum. I've been meaning to visit if for years. Maybe this spring I'll finally do it!