There are at least 110 places in New England that have the word “Devil” in their name, and forty-three of them are in Massachusetts. Hmmm. What does that say about the Bay State? There's Devil’s Hollow in Marshfield, the Devil’s Landslide in Wellesley, Devil’s Garden in Amherst, etc. And in Newbury, there is... the Devil's Den.

Last weekend Tony and I took a trip up to Newbury to visit the Devil's Den. The Den is actually a small cave located in an old, abandoned limestone quarry. There are a lot of old quarries in New England, but this one is really old. It was first quarried in 1697 and finally shut down in 1830. The quarry is not large but is very dramatic looking, which is why is probably why it got its devilish reputation.

Long after these quarries had ceased to have a commercial value, pleasure parties were accustomed, during the summer months, to seek rest and recreation there, beguiling the time with marvelous stories in which the Prince of Darkness was given a conspicuous place. In later years, the young and credulous found traces of his Satanic Majesty's footsteps in the solid rock, and discovered other unmistakable signs of his presence in that locality; and ever since the Devil's Den, the Devil's Basin, and the Devil's Pulpit have been objects of peculiar interest to every native of old Newbury. (Ould Newbury. Historical and Biographical Sketches, John James Currier, 1896)

That passage mentions several devilish places. The Devil's Basin was another nearby limestone quarry, filled with water, which I believe was about a half mile away from the Devil's Den (according to Volume 3 of Contributions to the Geology of Eastern Massachusetts, 1880). I'm not sure if the Basin still exists, but according to this site it was located south of the Devil's Den. That area now seems to be mostly landfill which is why I think the Devil's Basin is gone. The Devil's Pulpit was a large boulder nearby but we couldn't locate that either.

The Devi's Den still exists, and in the early 19th century young boys who lived nearby would perform a strange initiation ritual at it. They believed that a certain magic word had been written on the floor of the cave which would kill anyone who entered it. Certain precautions had to be taken before entering the cave to nullify this curse.

I suppose that no boy ever went to that place alone, and a sort of solemn ceremony attended his first visit with his older playmates, to a scene bearing an appellation ominous enough to call up every vague dread of his youthful heart. The approach on these occasions was rather circuitous, through the pastures, until an elevated mass of stone, standing quite solitary, was reached, designated as “Pulpit Rock.” To the summit of this, the neophyte was required to climb, and there to repeat some accustomed formula, I fear not very reverent, by way of initiation, and supposed to be of power to avert any malign influences to which the unprepared intruder upon the premises of the nominal lord of the domain might otherwise be subjected. (George Lunt, Old New England Traits, 1873)

In other words, after repeating the irreverent phrases from Pulpit Rock, (aka the Devil's Pulpit), it was safe to enter the Devil's Den. However, even then it was only safe to enter the cave with companions - never alone.

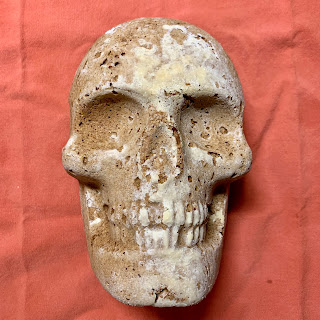

|

| Old graffiti at the Devil's Den |

Other than this curse and ritual, the Devil's Den had one other interesting feature. The Devil’s Den was made of limestone, but also had deposits of a mineral called chrysotile, a naturally occurring form of asbestos. Chrysotile is soft and chewy, and in the 19th century boys going into the cave would supposedly chew it. Hopefully, they avoided any dangerous side effects. Ingesting asbestos is probably scarier than than a Devil's curse!

I first learned about the Devil's Den while writing my first book, Legends and Lore of the North Shore. Back then, the Devil's Den was on private property, but it is now part of the 28-acre Jennie Lagoulis Reservation. It's worth a visit if you're in the area. Despite it's scary name and legend, you shouldn't be too spooked if you visit. The reservation is the site of a children's nature camp. If little kids can brave the terrors of the Devil's Den you can too.

*****

If you like New England legends, you might like my newest book, Witches and Warlocks of Massachusetts. It's available now wherever you buy books online!