The jack-o-lantern is a ubiquitous symbol of Halloween. All across America, people carve faces into pumpkins, placing them on doorsteps and windowsills as part of the holiday celebrations. Despite New England's modern connection with Halloween because of Salem's annual October festivities, Halloween really only became popular in New England in the latter half of the 19th century as more Irish and Scottish immigrants arrived here. The English Puritans and their descendants did not celebrate before then.

Still, despite this, the jack-o-lantern has deep roots in New England. It seems likely that people were carving jack-o-lanterns well before Halloween was even celebrated here, and that pumpkin carving became associated with the holiday only later. Read on if you dare...

Nathaniel Hawthorne: Giant Gems and Enchanted Scarecrows

Massachusetts author Nathaniel Hawthorne was apparently the first person to ever use the term "jack-o-lantern" in print. His 1835 story "The Great Carbuncle" is about a group of adventurers searching for a giant, glowing gemstone in the White Mountains. One of the adventurers tells his companions he will hide the gem inside his tattered cloak if he finds it.

‘Well said, Master Poet!’ cried he of the spectacles. ‘Hide it under thy cloak, sayest thou? Why, it will gleam through the holes, and make thee look like a jack-o’-lantern!’

It's not entirely clear what Hawthorne means by jack-o-lantern here. It sounds like it could be our familiar carved pumpkin lit by a candle, but the term jack-o-lantern also was used to mean ignis fatus, the glowing swamp gas phenomena also called willow-the-wisp. Either usage makes sense in the story. Halloween is not mentioned at all in "The Great Carbuncle," which was published before the holiday was celebrated in New England.

|

| Nathaniel Hawthorne |

However, a carved pumpkin does appear in Hawthorne's 1851 story "Feathertop," when a New England witch named Mother Rigby uses one as a head for her scarecrow:

Thus we have made out the skeleton and entire corporosity of the scarecrow, with the exception of its head; and this was admirably supplied by a somewhat withered and shrivelled pumpkin, in which Mother Rigby cut two holes for the eyes and a slit for the mouth, leaving a bluish-colored knob in the middle to pass for a nose. It was really quite a respectable face.

Mother Rigby is so pleased with her handiwork that she brings the scarecrow to life, and since this is a Hawthorne story the scarecrow learns a lot about human morality. Hawthorne does not use the term jack-o-lantern in the story, though, and Halloween is not mentioned.

John Greenleaf Whittier: Boyhood Memories?

The Massachusetts poet John Greenleaf Whittier mentions a carved pumpkin in his poem, "The Pumpkin," which was first published in 1846 (according to Cindy Ott's 2012 book The Pumpkin: The Curious History of An American Icon).

Oh, fruit loved of boyhood! the old days recalling,

When wood-grapes were purpling and brown nuts were falling!

When wild, ugly faces we carved in its skin,

Glaring out through the dark with a candle within!

Whittier was born in 1807. If he really carved faces into pumpkins when he was a boy, it would have been very early in the 19th century, long before Halloween was celebrated in New England. Whittier only refers to Thanksgiving in "The Pumpkin," but not Halloween, and he doesn't call the carved pumpkin a jack-o-lantern.

|

| John Greenleaf Whittier |

It's a little confusing, isn't it? The earliest instance historian Cindy Ott found where "jack-o-lantern" refers to a carved pumpkin comes from 1846. It appeared in a South Carolina publication called Tales for Youth, but again with no apparent connection to Halloween. It sounds as though people were carving pumpkins and using the term jack-o-lantern well before Halloween was celebrated, even if not always together.

A Demon and A Pumpkin in Rhode Island

Enough with the history, let's turn to the spooky stories. Many years ago, during the Revolutionary War, two young women named Hannah Maxson and Comfort Cottrell were staying at the Westerly, Rhode Island home of one Esquire Clark. One day while the Esquire was away on business, and his wife was sick in bed, the two young ladies decided to practice a little love magic.

They took a ball of yarn, and tossed it repeatedly down a well and then pulled it back up. As they did, they chanted some psalms backwards. The goal of this magic spell? To find the men they would marry.

As the sun set, Hannah and Comfort saw a tall figure walking up the road towards the house. They ran eagerly towards it, but their excitement turned to terror as they saw the figure had an enormous, misshapen head with two glowing, fiery eyes. This was no dream lover, but a demonic monster.

Hannah and Comfort ran into the Clarkes' house and locked the door, but the hideous creature pounded on it insistently. The young women hid behind Mrs. Clarke's bed in fear, listening with the sick woman as the monster tried to break into the house. The supernatural assault only stopped when Esquire Clark returned home. Seeing a demonic creature clawing at his front door, he said some prayers against evil, which sent the monster slinking off into the woods.

This story first appeared in a November 1860 issue of The Narragansett Weekly, and the author, Deacon William Potter, notes that Mrs. Clarke died from all the excitement. Hannah and Comfort vowed never to use magic again. But Deacon Potter includes a strange epilogue. He claims that the demon was really a hoax played by a young many who lived near the Clarkes. He put a carved pumpkin on his head to scare Hannah and Comfort, not anticipating his joke's deadly results. The neighbor only revealed his role in the story seventy years later.

It's a good spooky, cautionary tale. Young ladies - don't mess around with the occult. Young men - don't play stupid pranks that kill people. But despite the carved pumpkin, the story doesn't reference Halloween. And it's not called a jack-o-lantern.

The Sea Captain and Satan

Captain Snaggs was a wealthy sea captain who lived in Barnstable on Cape Cod. He had earned his riches the old-fashioned way: by selling his soul to the Devil. He had been young and foolhardy when he signed Satan's contract, but as an old man on his deathbed he was filled with regret. He could hear the Devil's hooves coming up the walkway towards his house, and Captain Snaggs didn't want to go to Hell. So he jumped out of bed, climbed out the window, and ran like... well, he ran like hell.

He ran down the length of Cape Cod to Orleans, where he hid in a hollow tree. But the Devil was hot on his heels, and could smell Captain Snaggs's soul. So Captain Snaggs ran again, this time to Wellfleet, where he hid in a cemetery.

The Devil was not far behind, so Captain Snaggs grabbed a pumpkin from a nearby pumpkin patch, carved a face in it, and set it up on a tall, white gravestone. Then he lit a candle inside of it and ran towards Truro.

When the Devil arrived in the cemetery he said to the pumpkin, "Your contract is up, Snaggs. I've come to take your soul." When the pumpkin didn't answer, the Devil poked the gravestone with one talon. "Do you hear me Snaggs? Ouch! You're awfully tough for an old man! Where'd you get those muscles?" He grabbed the gravestone and gave it a mighty shake. The pumpkin fell to the ground and shattered. Realizing he had been tricked, the Devil ran towards Truro with a demonic roar.

Captain Snaggs, meanwhile, had run all the way to Provincetown. He had reached the end of the Cape. There was no place left to go. When the Devil finally caught up with him, sulfurous smoke billowing from his nose and ears, Captain Snaggs stood there in terror.

With a tremor in his voice, he said, "All right, I'm ready. You can take me to Hell now."

The Devil looked puzzled and said, "Take you to Hell? We're in Provincetown, aren't we? We're already there."

As Elizabeth Renard notes in her 1934 book The Narrow Land, there are many variations on this story. The comedic ending always remains the same, but the name of the captain, the Cape Cod towns he visits, and the number of pumpkins involved all vary. You can listen to an excellent audio version of this tale at New England Legends, where the sea captain is named Jedidy Cole.

Renard also notes that this story is probably of late origin, so perhaps it was first told after Halloween became a popular holiday here. It's hard to say. Have a happy Halloween!

*****

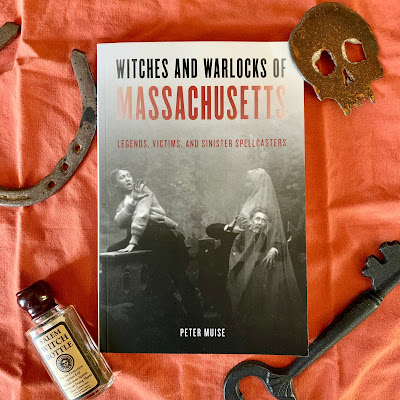

My new book, Witches and Warlocks of Massachusetts, was just released on Kindle recently. So now you can enjoy it either in paperback or on your device of choice. You can buy it wherever books are sold online.