On the twenty-fifth of December it was, that Mercy said, They (the invisible witches) were going to have a Dance; and immediately those that were attending her, most plainly Heard and Felt a Dance, as of Barefooted People, upon the Floor; whereof they are willing to make oath before any Lawful Authority.If I should now venture to suppose, That the Witches do sometimes come in person to do their Mischiefs, and yet have the horrible skill of clothing themselves with Invisbilities, it would seem Romantic. And yet I am inclinable to think it...

December 22, 2021

In 1692, Invisible Witches Danced in Boston on Christmas Day

December 13, 2021

Folklore Books (and Weird Fiction) for Christmas

Drinking eggnog. Wrapping gifts. Hallmark Christmas movies. These are all perfectly fine ways to get in the holiday mood, but sometimes I find myself wanting something different. Maybe something that will connect me to New England's historic roots, or evokes the increasing December darkness. Or maybe a folktale about murderous Christmas elves, or a tale about a snowy Massachusetts seaport with unholy secrets...

I've published this list before, but here it is again: those books that really put me in the Yuletide mood. I reread some of these every year. What are your favorite holiday folklore books or strange Christmas tales?

Ever wonder why Americans celebrate Christmas the way we do? Nissenbaum’s book traces the development of our modern child-focused and gift-focused holiday from the raucous holidays of the past. Several chapters in The Battle for Christmas focus specifically on early New England, looking at why the Puritans hated Christmas, which people celebrated Christmas despite it being banned, and how capitalism shaped the holiday. Christmas used to be a multi-week drunken orgy when the lower classes extorted food and liquor from the wealthy. Nissenbaum explains how it became a holiday where we sit peacefully around Christmas trees and exchange presents.

Do you exchange presents at Christmas time? Do you incorporate Santa Claus into you celebrations? Do you spend the holiday with your family? If you answered yes to any of these questions, you can thank Clement Clarke Moore. Moore was a prominent New York City clergyman who was annoyed at the drunken Christmas celebrations that kept disrupting his family’s peaceful home. Moore wrote “A Visit from St. Nicholas’ in 1823 to encourage a gentler, sober and more familial holiday. And it worked! Moore’s poem permanently shaped the way Americans and much of the world celebrate Christmas.

Again, no connection to New England, but lots of dark folk stories from Iceland. Many of them are set at Christmas time. The elves in these tales are not cute and whimsical, but instead are strange, dangerous, and often murderous. As are the trolls, witches, and lustful ghosts with shattered skulls who appear. Merry Christmas? This book is holiday reading for those of you who wish every holiday was like Halloween.

December 05, 2021

Meeting the Devil on Christmas Day

Ho ho ho! It's December, and Christmas madness is once again upon us. We just decorated our tree, I've had my first glass of eggnog, and I made fruitcake yesterday. Bring on the holidays.

Christmas is so widely celebrated in modern New England that you might not believe it was once viewed as a dangerous and possibly even Satanic holiday. But it's true! The following post (which I first published in 2017) explains more...

*****

In 1662, Rebecca Greensmith of Hartford, Connecticut was arrested and charged with witchcraft. She confessed to meeting the Devil, but she denied having signed a contract with him. Well, at least she hadn't signed one at the time of her arrest. Rebecca and the Devil were waiting for a special day to sign it: Christmas.

The Reverend John Whiting of Hartford wrote the following in a letter:But that the devil told her, that at Christmas they would have a merry meeting, and then the covenant should be drawn and subscribed. ... Mr. Stone (being then in court) with much weight and earnestness laid forth the exceeding heinousness and hazard of that dreadful sin, and therewith solemnly took notice (upon the occasion given) of the devil's loving Christmas. (quoted in David Hall's Witch-Hunting in Seventeenth-Century New England.)That sounds a little strange to modern readers. Why would the Devil love Christmas? Isn't it a holiday about hope, love and charity?

|

| Merry Christmas? |

Four-hundred years ago, Christmas was a very different holiday than it is today. It wasn't focused on family, gift-giving, and children. Instead, it was characterized by heavy drinking and public rituals that inverted the social order. Europe and its colonies were agricultural societies then, and food and alcohol were most plentiful during the late autumn and early winter. Crops had been harvested, herd animals slaughtered, and beer brewed. There was no more farm-work to be done.

In short, it was a great time to have a huge party. Wealthy people would feast themselves and their friends at home. People from the lower social classes, usually groups of young men, roamed around at night in disguise. The young men (called mummers) would usually target the homes of the wealthy, where they would perform a skit or song in return for food or beer. This is the origin of the wandering Christmas carolers so often portrayed in Christmas stories or movies. If they were denied entry or not given gifts for their performance, the mummers would retaliate with violence or by vandalizing property.

Some hints of this older-style Christmas can still be heard in the lyrics of Christmas carols. For example, "The Gloucestershire Wassail" describes men threatening a butler to give them good strong beer and demanding entry to a wealthy person's home:

Come butler, come fill us a bowl of the best

Then we hope that your soul in heaven may rest

But if you do draw us a bowl of the small

Then down shall go butler, bowl and all.

Be here any maids? I suppose here be some;The lyrics of "We Wish You A Merry Christmas" describe something similar:

Sure they will not let young men stand on the cold stone!

Sing hey O, maids! come trole back the pin,

And the fairest maid in the house let us all in.

Oh, bring us a figgy pudding;Christmas was raucous, drunken, socially disruptive, and occasionally violent. The Puritans valued order, sobriety, and hard work. They didn't want anything to do with Christmas.

Oh, bring us a figgy pudding;

Oh, bring us a figgy pudding and a cup of good cheer

We won't go until we get some;

We won't go until we get some;

We won't go until we get some, so bring some out here

During their brief tenure ruling old England the Puritans tried to suppress Christmas celebrations. The Puritans who colonized New England did the same. It was even illegal to celebrate Christmas in Massachusetts between 1659 and 1681. Anyone found doing so could be fined five shillings.

Puritan ministers in New England wrote sermons against Christmas. The Reverend Increase Mather wrote the following, equating Christmas with pagan deities and Satan:

The Feast of Christ's nativity is attended with such profaneness, as that it deserve the name of Saturn's Mass, or of Bacchus his Mass, or if you will, the Devil's Mass, rather than have the holy name of Christ put upon it. (A Testimony Against Several Prophane and Superstitious Customs, Now Practiced by Some in New-England, 1687).Mather mentions Saturn for a very specific reason. The Bible doesn't provide a date for Christ's birth, and the early Christian church fathers decided to place it on December 25 to coincide with pagan Roman winter holidays like Saturnalia, which venerated the harvest god Saturn. This compromise between Christianity and paganism was another argument the Puritans used for hating Christmas.

So there you have it. That's why the Puritans thought the Devil loved Christmas. Their efforts to suppress Christmas were modestly successful. Christmas wasn't widely celebrated in New England until the mid-nineteenth century. Christmas is now the biggest holiday in the United States. The Puritans would have blamed Satan, but I think it's just because people like to have fun.

November 29, 2021

The Ghost of Catherine's Hill: You Better Give Her A Ride

There's a lonely stretch of Route 182 in Maine. It's known as Black's Woods Road, and runs between Franklin and Cherryfield. This part of the state is quite rural, and the trees press heavily in on the road, particularly on a dark, moonless night.

The road climbs a small mountain known as Catherine's Hill, and if you're unlucky you might see Catherine herself one night while driving along Route 182. Catherine is a ghost, and appears as a forlorn young woman wandering the side of the road in an evening gown, either pale blue or white in color.

If you see Catherine, you should stop and offer her a ride. She'll tell you she's going go to Bangor. You should let her in even though it's a long drive and you might not be going that way. Otherwise, bad luck will come to you.

|

| Photo from Pinterest |

Here's an example. One night a salesman was driving along Route 182 when he saw Catherine walking by the side of the road. He was in a hurry and was also unnerved by the sight of a young woman in a formal gown alone in the woods. He instinctively knew something was uncanny about her, so he sped past without stopping. It was a fatal mistake. As he glanced in the rear view mirror, he saw Catherine suddenly sitting in the back seat of his car - without her head. Her bloody-necked corpse filled him with terror (of course!) and he lost control of the car. He died instantly when it hit a tree.

Some legends say Catherine was driving to her prom with her boyfriend when they got in an accident and both died. She was decapitated, and now walks along Route 182 trying to find her boyfriend. Sometimes Catherine is even seen wandering headless along the side of the road. You should still stop and offer her a ride if you see her in this condition, unless you want something bad to happen to you. The bad luck isn't always immediate. Sometimes it takes a few days, but it always comes. Better to just offer her headless corpse a ride.

There are a few variations of the legend. Maybe she died on the way to her wedding, and maybe she died in the 1800s in a carriage accident. Despite the minor fluctuating details, the core of the story remains the same: offer Catherine a ride or face the consequences.

To me, the legend feels like a variant of the classic ghostly hitchhiker story. In that story, which is told all across the country, a driver picks up a young woman who is hitchhiking. The driver agrees to take her to her destination. Upon reaching the destination, the young woman vanishes. The driver asks somebody at the destination if they can explain what happened, and is told, "Why, that young woman was my daughter/sister/grandmother/etc. and she died in an accident this very night many years ago!" The Catherine's Hill legend includes some of these elements (the young woman who died, someone giving her a ride) but omits the revelation at the end. Instead, it substitutes a curse - anyone who doesn't offer Catherine a ride suffers a horrible fate. It's a nice twist on a classic story.

This story has apparently been told for many years, but I just learned about it recently when someone who heard me on a radio show emailed me about it. Thank you Larry! It is a great story! If anyone is interested in learning more, this article from the Bangor Daily News is quite good. You can also check out Marcus Librizzi's book Dark Woods, Chill Waters: Ghost Stories from Down East Maine (2007).

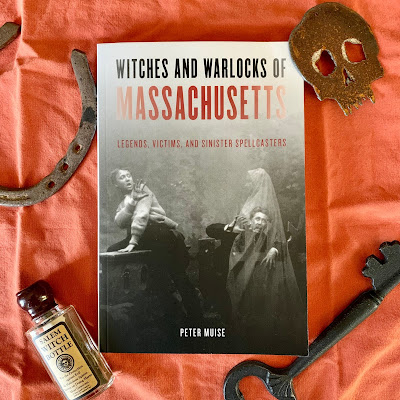

Speaking of books, they make good holiday gifts. My new book, Witches and Warlocks of Massachusetts, is now available wherever books are sold online. It's the perfect gift for almost anyone!

November 21, 2021

Plymouth, 1734: A Haunted Mansion and A Court Case

It's Thanksgiving week, so here's a spooky story about a haunted mansion from Plymouth, Massachusetts. It's spooky if you believe in ghosts, but it's even spookier if you've ever been a landlord. Read on...

In 1725, a wealthy sea captain named Thompson Phillips married Hannah Cotton, the daughter of Reverend Josiah Cotton of Plymouth. Shortly after their marriage, Phillips built a large mansion in Plymouth for him and his new wife to live in. It was one of the finest homes in town.

Sadly, Thompson Phillips drowned in a storm while sailing to Jamaica. Shortly after remarrying, his widow also died, from smallpox. Ownership of the mansion passed to Reverend Cotton.

Reverend Cotton lived on a prosperous farm just outside of town and did not really want to own a large empty mansion. He tried to sell the house, but the local economy was in a slump and he could not find a buyer. He decided to rent it out and soon found some tenants.

Foremost among them was John Clarke. Clarke worked as a joiner, a type of skilled woodworker. He renovated several rooms into workshops, and lived in the mansion with his family and some apprentices. His colleagues Thomas Savery and Samuel Holmes and their families also moved into the mansion, as did a spinster named Ann Palmer. For a while all was good. The tenants lived and worked in the deceased sea captain's mansion, and Reverent Cotton collected rent from them.

Gwendolen Raverat, Clerk Saunders' Ghost, 1918 woodcut.

The good times didn't last. In January 1733, the tenants began to hear strange noises. Sometimes they sounded like the death moans of a dying person, and at other times like a cane being struck against the walls. The tenants couldn't discern where the noises were coming from. Adding to the weirdness, doors and cabinet drawers would open on their own accord.

Various people, both inside and outside the house, also reported strange lights. For example, one night Mary Little, who lived near the mansion, saw a strange blue light ("a pale blewish light") in one of the upstairs windows. She watched the light for nearly 30 minutes before it disappeared. The next morning she asked John Clarke's wife if the apprentices had been up in the attic late at night with a candle. Mrs. Clarke looked surprised. No one had been upstairs at all!

News of the strange phenomena began to spread through Plymouth, and soon nearly everyone in town believed the mansion was haunted. Large crowds gathered outside the house at night trying to see the weird blue lights or hear the mysterious groans.

Reverend Cotton was unhappy about the rumors and believed they were false. Several weeks before the alleged hauntings became public, he had argued with John Clarke. Cotton wanted to move one of his son-in-laws into the mansion and wanted John Savery, Clarke's colleague, to move out. Clarke was infuriated. He shouted that the house was haunted and that he, and all the tenants, would move out. Cotton didn't believe the house was haunted and thought the rumors about ghosts were just a way to get back at him.

By October of 1733, all the tenants had vacated the mansion, claiming they were unable to live with the supernatural phenomena. Reverend Cotton attempted to find new ones, but no one was willing to move in. Many people believed the house was haunted, and those who were skeptical didn't want to deal with the large crowds of gawkers who gathered outside almost nightly.

Cotton finally took his former tenants to court. They owed him unpaid rent and had broken their lease, but he thought it unlikely he'd be able to get recompense for that in court. Instead, he sued them for slander. The case was heard on March 5, 1734 in the Plymouth County Inferior Court of Common Pleas. Reverend Cotton was ill and could not attend the trial, but his lawyer, John Cushing Jr., grilled the defendants. He argued they had lied about the hauntings to break the lease and prevent Cotton from renting to future tenants. After all, Cushing said, it was the 18th century. How could anyone still believe in ghosts, witches, and demons?

Cushing (and Cotton, who had helped develop their legal strategy), underestimated the jury's belief in the supernatural. The jury believed the house was indeed haunted and also believed Cotton's former tenants were telling the truth. They found them innocent of slander. Cotton appealed the case and brought it to Plymouth Superior Court a month later. Once again a jury found the defendants innocent, and this time also required Cotton to pay their court costs. Clearly, people in Plymouth believed in ghosts.

Reverend Cotton gave up trying to sue the tenants, and eventually he moved into the allegedly haunted mansion with his own family. They lived there for more than five years, and never experienced any strange phenomena. Cotton also wrote an essay decrying superstitious beliefs, but sadly never published it. The building was eventually sold, and still stands on King Street in Plymouth today. As far as I know, no one has reported any ghosts since.

My source for today's post was Douglas Winiarski's article "'Pale Blewish Lights and A Dead Man's Groan: Tales of the Supernatural from Eighteenth-Century Plymouth,"which appeared in The William and Mary Quarterly, Oct. 1998, Vol. 55, No. 4, p. 497 - 530.

If you want to read more supernatural tales from the Bay State, I recommend my new book Witches and Warlocks of Massachusetts, which is available wherever books are sold online. It's a perfect Christmas gift too!

November 11, 2021

The Plymouth Vampire of 1807

Thanksgiving is fast approaching, and many people associate the holiday with Plymouth, Massachusetts. This is where the Pilgrims held a feast in 1621 that is sometimes said to be the "first Thanksgiving." That may not really be the case, but it's still a beloved American myth that is remembered every year around this time.

But why does no one talk about the Plymouth vampire in November?

Most people don't associate vampires with Plymouth, but maybe they should. According to folklorist Michael Bell's excellent 2001 book Food for the Dead: On the Trail of New England's Vampires, there was at least one documented case of vampire belief in Plymouth.

Note that I coyly wrote "documented case of vampire belief." There were no real vampires in New England, but according to Bell's research some people did believe they existed. The New England vampires were not like the Hollywood, pop-culture bloodsuckers we know today. Hollywood vampires kill their victims by drinking blood. New England vampires killed people with tuberculosis, and only killed members of their own families.

Tuberculosis, or consumption as it was called in earlier centuries, is an infectious bacterial disease that affects the lungs. People with latent tuberculosis show no symptoms, but those with active tuberculosis are afflicted with violent (and often bloody) coughing, fever, and severe weight loss. About 50% of people with active tuberculosis die if the disease is not treated. Tuberculosis spreads when an infected person coughs, sneezes, or even speaks. It spreads easily in crowded conditions, like prisons, asylums, or small New England farm houses inhabited by large families.

If one member of a family died from the disease, quite often other members would slowly waste away and die from it as well. People had many false ideas about what caused tuberculosis until Robert Koch identified mycobacterium tuberculosis in 1882. In some parts of New England, people believed it was caused by a dead person feeding off their living relatives. If one person in a family died from the disease and then others developed symptoms afterwards, the still-living relatives might blame the person who died. They thought the dead person was feeding off their living family members from the grave.

Michael Bell documents 18 cases of New England vampirism in Food for the Dead, from 1793 to 1892. I assume there were more that went unrecorded. The Plymouth vampire case occurred in 1807, and was first mentioned in an 1822 Philadelphia newspaper article which was reprinted in a Plymouth newspaper. The author of the article writes about Plymouth as if it were a superstitious backwater:

In that almost insulated part of the State of Massachusetts, called Old Colony or Plymouth Colony, and particularly in a small village adjoining the shire town, there may be found relics of many old customs and superstitions which would be amusing, at least to the antiquary...

There was, fifteen years ago, and is perhaps at this time, an opinion prevalent among the inhabitants of this town, that the body of a person who died of a consumption, was by some supernatural means, nourished in the grave of some one living living member of the family; and that during the life of this person, the body remained, in the grave, all the fullness and freshness of life and health...

The author goes on to explain that in 1807, of a Plymouth family of 14 children and two parents, only the mother and son had not died of tuberculosis - and they were both extremely ill with it. Some neighbors decided to help the family by digging up the grave of the daughter who had most recently died. They suspected she was feeding on her mother and brother. If the sister's corpse looked fresh and alive, this would confirm she was the one causing the illness. To stop her from feeding, they would turn her corpse face down in its coffin. This would prevent her from stealing the vitality of her brother and mother.

At the appointed hour they attended in the burying yard, and having with much exertion removed the earth, they raised the coffin upon the ground; then, displacing the flat lid, they lifted the covering from her face, and discovered what they had had indeed anticipated, but dreaded to declare. Yes, I saw the visage of one who had long been the tenant of a silent grave, lit up with the brilliancy of youthful health.

Sadly, the exhumation did not work. The shock of seeing his sister's corpse was too much for the surviving brother - he died two weeks later. The mother lived for a year before finally succumbing to the disease as well.

A local physician wrote a rebuttal in the next issue of the Plymouth newspaper. He claimed no family of sixteen had died of tuberculosis, and also tried to argue that the people in Plymouth were not superstitious:

During a residence of nearly forty years in the district referred to, and favoured with opportunities of correct observation regarding this subject, the writer of this reply has not been made acquainted, with but one solitary instance of raising the body of the dead for the benefit of the living; and this was done purely in compliance with the caprice of a surviving sister...

You can see why I said he "tried to argue," because he states that at least once a body was exhumed to prevent it feeding on the living. But you know, only once.

That local physician might have found some comfort knowing that the vampire belief in Plymouth was not as extreme as it was in other parts of New England. The people in Plymouth believed simply turning the corpse face down would stop it from feeding. In other places, people believed the vampiric corpse's lungs and liver had to be burnt to ashes, and then ingested by their living relatives. Yes, you read that right. In order to prevent their vampiric relative from sucking their life out, people would eat or drink the ashes of their liver and lungs.

It sounds almost unbelievable, but Bell has very good documentation in Food for the Dead. If you're interested in the topic I recommend his book highly. It would make interesting reading material before you get together to dine with your family at Thanksgiving.

*****

Thanksgiving is the start of the holiday shopping season. Might I suggest buying copies of my new book Witches and Warlocks of Massachusetts for the people in your life? It's available wherever you buy books online.

October 31, 2021

The Devil and Elizabeth Knapp: Demonic Possession and Witchcraft in 1671

October 17, 2021

Jack-O-Lanterns: Demons, Gemstones, and New England Origins

The jack-o-lantern is a ubiquitous symbol of Halloween. All across America, people carve faces into pumpkins, placing them on doorsteps and windowsills as part of the holiday celebrations. Despite New England's modern connection with Halloween because of Salem's annual October festivities, Halloween really only became popular in New England in the latter half of the 19th century as more Irish and Scottish immigrants arrived here. The English Puritans and their descendants did not celebrate before then.

Still, despite this, the jack-o-lantern has deep roots in New England. It seems likely that people were carving jack-o-lanterns well before Halloween was even celebrated here, and that pumpkin carving became associated with the holiday only later. Read on if you dare...

Nathaniel Hawthorne: Giant Gems and Enchanted Scarecrows

Massachusetts author Nathaniel Hawthorne was apparently the first person to ever use the term "jack-o-lantern" in print. His 1835 story "The Great Carbuncle" is about a group of adventurers searching for a giant, glowing gemstone in the White Mountains. One of the adventurers tells his companions he will hide the gem inside his tattered cloak if he finds it.

‘Well said, Master Poet!’ cried he of the spectacles. ‘Hide it under thy cloak, sayest thou? Why, it will gleam through the holes, and make thee look like a jack-o’-lantern!’

It's not entirely clear what Hawthorne means by jack-o-lantern here. It sounds like it could be our familiar carved pumpkin lit by a candle, but the term jack-o-lantern also was used to mean ignis fatus, the glowing swamp gas phenomena also called willow-the-wisp. Either usage makes sense in the story. Halloween is not mentioned at all in "The Great Carbuncle," which was published before the holiday was celebrated in New England.

|

| Nathaniel Hawthorne |

However, a carved pumpkin does appear in Hawthorne's 1851 story "Feathertop," when a New England witch named Mother Rigby uses one as a head for her scarecrow:

Thus we have made out the skeleton and entire corporosity of the scarecrow, with the exception of its head; and this was admirably supplied by a somewhat withered and shrivelled pumpkin, in which Mother Rigby cut two holes for the eyes and a slit for the mouth, leaving a bluish-colored knob in the middle to pass for a nose. It was really quite a respectable face.

Mother Rigby is so pleased with her handiwork that she brings the scarecrow to life, and since this is a Hawthorne story the scarecrow learns a lot about human morality. Hawthorne does not use the term jack-o-lantern in the story, though, and Halloween is not mentioned.

John Greenleaf Whittier: Boyhood Memories?

The Massachusetts poet John Greenleaf Whittier mentions a carved pumpkin in his poem, "The Pumpkin," which was first published in 1846 (according to Cindy Ott's 2012 book The Pumpkin: The Curious History of An American Icon).

October 09, 2021

The Witches of Norton: Magic, Animals, and Poverty

Well, it's October now, the month which many people call "Spooky Season." Even thought it's always spooky season here at the New England Folklore blog, I do love this month and Halloween. It's the season for pumpkins, ghosts, and of course witches.

New England is full of witch legends. Although the Salem trials are the most famous witchcraft incident in Massachusetts, lots of other cities and small towns held witch trials or have legends about witches. For example, Norton, a small town in the southeastern part of the state, was supposedly home to three witches in the 1700s.

The most famous alleged witch in Norton was Ann Cobb. I am not sure exactly why Ann was suspected of witchcraft, except for the following. One day she went into town to purchase some items at the general store. She lived about two miles away from the town center, but arrived there only minutes after leaving her house. This was quite fast, so her neighbors suspected she had used supernatural means to travel so quickly. Perhaps she flew, or was transported by some sort of evil spirit? Historical sources don’t specify her neighbors' exact suspicions, but the event was so memorable the town named a bridge after her. (It still exists today, and bears the name Witch Bridge.) Apparently, it didn’t take much to be considered a witch in Norton. Ann Cobb was quite poor and was supported financially by the town in her old age. She died in 1798.

Dora Leonard was another Norton woman suspected of witchcraft. She supposedly caused various forms of mischief around town, like magically setting farm animals loose so they could wander free. Two boys also said she once caused them to miss a squirrel they were shooting at. Despite having a clear shot at a the animal, the boys missed it repeatedly.

As they walked home, frustrated, they noticed a large cat watching them pass by. They believed the cat was really Dora and that she had used witchcraft to make them miss the squirrel. (It seems more likely they were just bad shots looking for someone to blame.) Much like Ann Cobb, Dora Leonard was poor and had to be supported by the town in her old age. As she lay dying in 1786, her house was supposedly filled with strange and terrible noises that frightened away the people attending to her death. Those details about her death are a standard trope in witch legends from New England.

The third alleged witch in this small town was Naomi Burt. Local historian Duane Hurd wrote of her in 1859: “Naomi Burt was also accounted a member of the mysterious sisterhood of witches, and by her wonderful powers gave some trouble to those who fell under the ban of her displeasure.” Wagons lost their wheels when they passed her house, and oxen escaped their yokes. Children held their breath in fear as they ran past her home lest she bewitch them. Sadly, Naomi Burt took her own life on July 4, 1808, a harsh reminder that while these old tales of witchcraft are entertaining to read, it was hard to really be the person they were about.

The Salem witch trials were the last trials of their kind in Massachusetts. They occurred in 1692, but people in New England continued to think their neighbors were witches for hundreds of years after that. They didn't bring them to court anymore, but instead whispered, gossiped about, and sometimes physically threatened anyone they thought was a witch. Often those suspected were poor women who depended on their neighbors' charity for survival. That's clearly the case with the Norton witches. Resentment at having to support someone easily curdled into hatred and accusations of witchcraft.

In many cases, suspected witches were accused of making animals misbehave or preventing hunters from shooting their prey. Maybe this is because the witches were associated with the natural world more than the human world, as evidenced also by their ability to transform into animals. Perhaps they are protecting the animals from harm or mistreatment. "Free the oxen!" It's the more modern, romantic interpretation.

James Audubon, The Dusky Squirrel

On the other hand, people in the 18th century would have had a very different opinion. A farmer depended on his oxen the way a modern person depends on their car, and a family needed their livestock for food. Any disruption threatened someone's ability to survive. And even though I love squirrels, those two boys probably would have eaten that squirrel for dinner if they killed it. Maybe they went to bed hungry that night.

Just to be clear, I am not saying these women were witches. They weren't. They were social outcasts accused of witchcraft. People just projected their fear onto them. Fear of hunger, of poverty, of illness, and of death. These are real fears we all have, but hopefully we don't project them onto our neighbors. So what's spookier: legendary witches, or real people who actually accused their neighbors of being witches? I think it's the latter.

If you want to read more witch stories for Spooky Season, and I know you do, I'll recommend my new book Witches and Warlocks of Massachusetts, which was just published by Globe Pequot last month. It contains dozens of legends and historical accounts of witches from across this glorious state. It's available wherever you buy books online, and hopefully in your local bookstore as well.

September 29, 2021

Book Review: Mythical Creatures of Maine

September 23, 2021

The Barren Circle: A Maine Witch's Cursed Grave

As this blog's readers know, I love stories about witches. I also love cemeteries. So I really, really love this story from Bowdoin, Maine since it involves a cemetery and a witch.

First, a little clarification. Bowdoin, Maine is a small town in Sagadahoc County, Maine, and is pronounced "bow-din." It shouldn't be confused with well-known Bowdoin College (also pronounced "bow-din"), which is nearby in Brunswick, Maine. Both are named after the Bowdoin family, who played important roles in Maine's 18th century history, but they are not the same place.

Bowdoin, Maine looks like a charming small town, but small towns often hide terrifying secrets, as every Stephen King fan knows. According to a local legend, Bowdoin's terrifying secret is inside North Cemetery on Litchfield Road. Here, a circle of cedar trees grows around a barren patch of earth at the back of the cemetery. This, people say, marks the grave of a witch.

Or, perhaps more likely the grave of an innocent person labeled a witch. Many years ago, a woman named Elizabeth was accused by her Bowdoin neighbors of witchcraft. An angry mob dragged her into the cemetery and hanged her from a tree. After she was dead, they cut her down and buried her. Since that time, the trees have grown up in a circle around her grave, but nothing grows on the grave itself. The earth remains barren.

This barren circle is said to be cursed. Anyone who steps on the ground there will meet a grim death. According to one story, one night three teenage boys dared each other to step onto Elizabeth's grave. They all took the dare, and all soon regretted it. The three of them died soon afterwards, each succumbing to a gruesome fate.

|

| Image of the barren circle by Dori Upham on Find A Grave |

Some accounts say Elizabeth was hanged in the 1800s, which makes me suspect the story is probably purely legend. The Salem trials were the last time anyone was executed for witchcraft in New England, and they ended in 1692. I suppose Elizabeth could have been murdered by a mob, but other details of the story (like Elizabeth's lack of a last name) make me think it's just a legend.

Of course, saying it is "just" a legend sounds dismissive, which I don't intend. Legends and myths have power, whether or not they're based on fact. If I visited North Cemetery I wouldn't step onto that barren circle, would you? I'm skeptical when I'm sitting here at home, but put me in a lonely cemetery and I get a lot more superstitious. Why take the risk? That's the power a legend has.

Photos on this site show that people have left coins and flowers on the barren circle. Are they literal offerings to Elizabeth's restless spirit, or do people just feel compelled to leave an acknowledgment of the legend?

I first learned about this legend from the Jumping Frenchmen podcast. I've never been to Bowdoin, Maine but would like to visit someday. In the meantime, I did enjoy this video from the Maine Ghost Hunters that documents their visit to Elizabeth's grave. A misty day, a country road, an old cemetery - very evocative!

If you like witch stories, please consider buying my new book, Witches and Warlocks of Massachusetts, which just came out this month. It's available wherever you buy books. Lots of spooky stories and accounts of historical witchcraft!